The Death of Music

Introduction

Creation of music is as old as the humanity itself. In the modern musicological perspective, music is formed of four fundamental elements: rhythm, melody, harmony, and tone colour. Some include a fifth element of "form", which I shall agree. From the "rhythm" perspective, we have been making music for as long as we do not remember. From the "melody" perspective, it is for fifty millennia. From the "harmony" perspective, we have been making it for at least a millennium. If we consider "tone colour", we have been composing for at least five centuries. Whenever you take the origin, the craft of music has never faced the problems that it does in our time. Every time it got into a loop, a genius revolutionist came up with a brand new school and created new bricks for his successors to build. But now, it looks that we are out of tools to compose new & original work.

I wish I found some better sounds no one's ever heard

I wish I had a better voice that sang some better words

I wish I found some chords in an order that is new

I wish I had a better voice that sang some better words

I wish I found some chords in an order that is new

The three lines from Stressed Out, Twenty One Pilots song, the brave and honest words that may make this whole article look useless, that briefly summarize the crisis of which they also are a part.

Although I am going to give some reasonable causes that led to the situation, I would like to clarify that I am not going to try to propose any solution for the problem. The reason for that will manifest as I am going to give the causes: it is certainly a gross overstatement that we are out of geniuses for the required revolution that may impact the world of music as it did a couple of times in the past. The problem does not look promising for the existence of a solution due to the fundamentals upon which the western music system is based.

This is enough of words to get the reader into a mood of despair. Therefore let me try to define the problem straight. But before, let us have a look at what kind of revolution that is, in my opinion, never to come in our time.

Revolutionary Thresholds in The History of Music

Consonance

Rhythm was probably the first element of music that emerged. Regardless of the age or the realm, effective use of rhythmic sound depended upon the use of small integers, like 2, 3, 4. A rhythmic music should consist of sound patterns that repeat 2, 3, or 4 times at a time. This is actually what defines rhythm. If it does not recur, or if it recurs a higher number of times; it either departs from being rhythmic and gets closer to being just a noise, or becomes too complicated for the weak short-term memory to grasp a pattern. Hence it was all about simple small integers.

Almost any intellectual phenomenon can be traced back to ancient Greek. Music is no exception. The use of small integers in pitches of the sound, after rhythm, was probably the first great revolution, that introduced a whole new realm wherein the slightest semblance of what we know as 'music' can then be made. It is accepted that it was Pythagoras who "discovered" consonance. It was already known that the pitch of the sound that an iron rod creates when hit is related to its length. What Pythagoras noticed was that when two different rods are hit at the same time, if the ratio of their lengths constitute a small-integer-ratio, like 2:3, the collective sound they produce sounds more likable compared to those of lengths of complex ratios.

This was the first known discovery of consonance and it deeply influenced the way western music system is build.

Twelve Tone Scale

Because the number two is the simplest number one can have apart from unity and naught, tones whose frequencies share a ratio of 2 are heard so harmonious that people perceive them as the same note. For that reason, for all of the music schools, genres, and periods; notes with frequency ratio of 2 are accepted as the same notes, just one octave apart. Inducing this axiom, one can say that all notes are the same if their frequency ratio is a power of 2. Hence, all of the other notes can be found by multiplication/division operations with simple integers except 2 and its powers.

Take a reference note and call it Do. Now apply small integer ratios to its frequency to find new notes. Multiply by 3, you get So. Divide by 3, you get Fa. Those are the three base notes for an Ionian scale: tonic, subdominant, dominant.

Now multiply each base note by 3 and 5 (since 4 is going to lead to the same note because it is a power of 2):

Do: x3 -> So, x5 -> Mi

So: x3 -> Re, x5 -> Ti

Fa: x3 -> Do, x5 -> La

After the found notes are altered by powers of two to make them closer, you get 7 notes in order: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Ti. And here are the 7 notes in a C major / A minor scale. Regardless of the era or the school (except for 2nd Viennese School) all of the western music, in smaller perspective, use the same scale; only transposed or modulated.

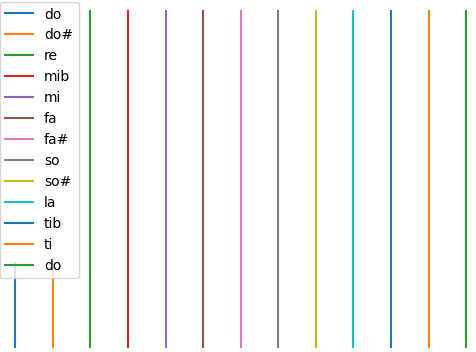

When the frequencies of those 7 (+1 to complete the scale with an additional do) notes are displayed on a logarithmic scale, they look like this:

Do you feel like that is a grid with some missing parts? It is as if all of them are evenly spaced except the gap size is either one or two units. This is probably the most beautiful mathematical coincidence in the history of music that led to what it is going to become. Yes, coincidence. Because even if they look like it, they are not evenly spaced, even if you fill in the gaps. They slightly vary around an evenly spaced grid. But they look like it in this is what matters, since our ears are not sensitive enough to differentiate small changes in frequencies. Hence, let us act like they are part of an evenly spaced grid.

After you fill in the five gaps that look bigger with respect to the smaller two, you get twelve different notes. Ta ta! The good old twelve tone scale, which is the fundamental upon which the western music is built.

It is both uncertain when exactly this pattern emerged and whether it is actually a point in time or a part of an evolution. Nevertheless, it is all about Pythagoras' good old small-integer-ratio discovery and a bit of mathematical coincidence.

Modulation, Drama

In terms of harmonic/polyphonic complexity, we can divide the history into two parts: before Bach and after Bach. Before Bach, composers generally only used one tonal centre or a few, with one main centre, for all of the music. Modulation, which means a temporary or permanent change in the tonal centre, were only made to change the tonal centre to another very related one, like dominant, subdominant, or relative minor. Johann Sebastian Bach was the first one who could use all of the twelve notes in a piece of music with reasonable-pleasant modulations and use even more than 10 tonal centres in a piece of music if needed.

Successors of Bach liked the ideas and methods that Bach proposed. Mozart, even he might be the greatest musical genius ever, was not really a fan of modulations other than those that changed tonal centre to very related ones. Although he might have created the most beautiful and catchy melodies in the history of music, his contributions to the techniques, music theory, and musicology are marginal; compared to the other big guys like Bach, Beethoven, Wagner...

Beethoven, a big admirer of Bach, adopted the idea of modulation and reflected that in all of his mid to late period music. He always wanted to write fugues as good as Bach and the latest works of his are nothing other than efforts showing his admiration to Bach-style fugue writing. Though he was not as great fugue writer as Bach, his strong place in the history of music comes from his use of music to tell stories, which would be difficult without the effective use of modulations.

Don't get me wrong when I tell you that Beethoven told stories with music. It is not necessarily a story that a song tells with lyrics. It does not necessarily have to be an ordinary story like "two people in love", "a king trying to retain his title" whatsoever. But you could feel the story in his music. It had introduction, development, conclusion; it felt like suffering, loving, sacrificing; it made you smile, weep, dream. It involved all the things that a story can do to someone, except the story itself. He is not considered the initiator of Romantic Period for no reason after all.

Wagner, who was in my opinion a Beethoven sequel, extremely extended the use of drama and modulation. With him, music has reached in immense capability of story-telling that in a work of art consisting of theatrical, literary and musical elements, which is an opera, the music played the leading role to tell the stories. It is vaguely known that Wagner composed pieces of music in smaller scale, and looked for historical narratives to complement the music to constitute the opera. His use of extreme chromaticism, rapid and ambiguous tonal centre changes, rich use of orchestral texture and loads of techniques affiliated to him made it seem like the conventional tonal music has reached its ultimate summit. Saying that it is difficult to make music that included masterful, rapid, and natural-sounding tonal centre changes and complex harmonies and not sounding like a Wagner wannabe; is a gross understatement. But it is worth to note that no matter how ambiguous or rapid the modulations in Wagner's music are, it is still as tonal as possible and meets the foundations/scales proposed since Pythagoras's discovery of consonance.

Atonal Music: A Failed Revolution

A lot of modernist musicologists or historians won't like the sub-heading but I am ready to face what is to come.

After Wagner made it extremely hard to build new harmonic methods and make contemporary sounding original music, people looked for new methods to discover the limits of music. Wagner's latest works, noteworthily Tristan und Isolde, are considered what opened the gates to the path that was to arrive at Atonality. Tristan und Isolde, which is in my opinion the greatest piece of art in all of the history of aesthetic crafts, is really ambiguous in terms of tone that an uneducated ear might not hear a clear tone and get lost at some parts. But that by itself does not prove that Wagner got away from tonality, as a deaf person not hearing Mozart saying Mozart does not make music won't prove any point either.

*** TO BE CONTINUED ***